It is great to see OpenAI Heading to Hollywood To Pitch Revolutionary “Sora.” It is also crazy to see A Surprising Number of Consumers Believe AI Could Make Better Shows and movies Than Human Creators.

If you’ve explored Generative AI on the creative front, you can recognize not only its vast potential but also the indispensable role of human creators in pushing AI to do better, to go against its very nature of pattern-finding to pattern-breaking. It would be great to see if this “pushing” is precisely what Sam Altman and OpenAI are diving into with creatives in Hollywood. But I’m also keen to see how much they’re delving into interactive narrative over fixed narrative. Interactive narrative, much like the quest for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), remains a profound aspiration shared by visionaries such as Janet Murray in “Hamlet on the Holodeck, the Future of Narrative in Cyberspace“, Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling, and many others.

I was in computer animation school in Minneapolis when I first heard the concept of the Metaverse and interactive narrative. The Metaverse was a network of virtual worlds you could enter as a participant. While these virtual worlds didn’t include social tools as Mark Zuckerberg envisions for his, they did imagine stepping into story worlds—imagine stepping into Star Wars. Like many, I was hooked on the vision and would follow attempts over the years to try and make it a reality. I would even try a couple of experiments myself. For me, all those attempts, the cycles of excitement, and their dissipation mirror those of AI winters – though with less hype and investment.

I am happy to see Generative AI, OpenAI, and others primed to ignite the next wave of experimentation around interactive narrative. For all the reasons Ben Thompson points out in his post “Sora, Groq, and Virtual Reality,” I’m encouraged that Generative AI can overcome the biggest barrier to interactive narrative and empower creatives to do what they do—discover the film grammar of this new medium, to discover the grammar of interactive narrative.

But before I discuss the biggest barrier to interactive narrative, let’s take a trip down memory lane and the winters of interactive narrative.

The winters of interactive narrative

1. Early video games (Atari)

It started with the first video games. Bing Gordon dreamed of having a computer make you cry. He and his colleagues would go on to build the wildly successful Electronic Arts, but had to give up on their dreams of a New Hollywood.

“We see farther”, we crowed. We predicted the games business would develop to stand side by side with the $20 billion annual revenues of movies and recorded music. We foresaw a day when a New Hollywood would be created by “software artists” who harnessed Moore’s Law into a new category of art. We believed that their digital games would one day deliver the kind of emotional experiences we all enjoy in movies, what Stephen Spielberg describes as “sitting back and being washed over with emotion.

But we fell short of the lofty creative goal of “Can a Computer Make You Cry?” because we didn’t develop new models of character and narrative. Floyd, the robot friend in Steve Meretsky’s Planetfall, was a heart-warming sidekick but, no matter what words we typed into the Infocom parser, he died a sacrificial, text-only, death for us.

Bing Gordon

2. CD games (Myst)

Myst emerged as a groundbreaking success, inspiring a wave of imitators eager to utilize the expansive CD storage capacities to craft the rich, immersive content essential for interactive narrative and world-building. In a way, it spurred a small interactive movies industry with such hits as Silent Steel. I had the privilege of working with many of the team behind Silent Steel at their later company, building virtual training simulations for the likes of the FBI on virtual worlds. It was also here that I came to truly understand the biggest barrier to interactive narrative.

3. Virtual worlds (Second Life)

Second Life introduced much of the world to virtual worlds and spawned many imitators. But just as Second Life didn’t ultimately usher in the Metaverse, its dreams around interactive narrative also faded.

Why so cold? The causes of recurring winters

Many might point to the immaturity of the technology for the recurring winters, but I would argue that creatives can spin narrative magic around almost anything. Look at Kamishibai picture cards in Japan or single-sentence story contests. Constraints spur creativity. The problem I and others experimenting with this found the problem to be the opposite: the lack of constraints. A lack of constraints prompted the need to create more content.

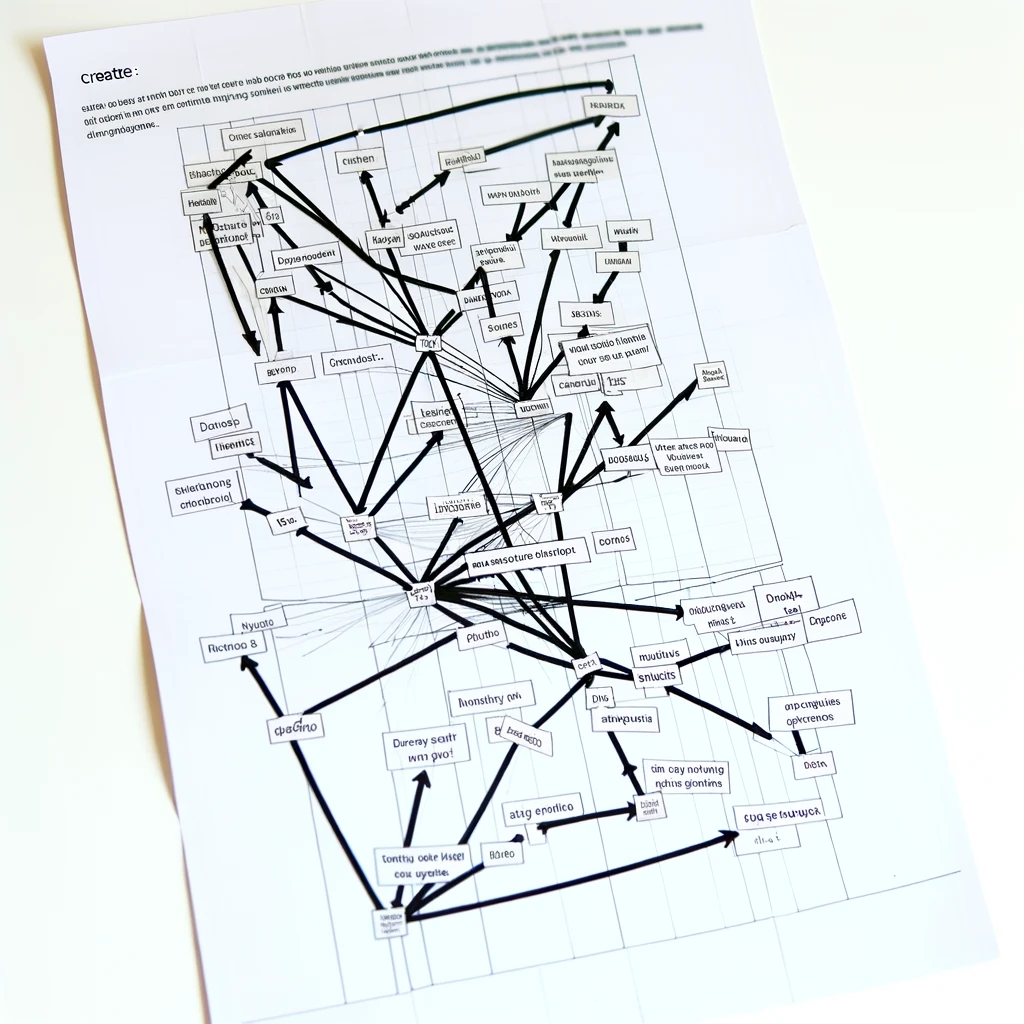

Interactivity is expensive. I can capture it best by comparing it to screenwriting. Think of how one creates a movie: the screenwriter dreams up all the potential paths a story may take and picks the best one through pain and toil. Then, an expensive production process starts on that single path. For interactive narrative, you need to not only create content for the other paths, but these alternative paths can be seen as inferior to the screenwriter selected path. Imagine if you are a second or fifth-unit director filming plot path twenty-two. Combined with that, as the viewer, you, too, would be on what can be seen as an inferior path. You can imagine the screenwriter yelling for you not to go down that path.

Even if you use a solution that doesn’t involve paths (and everyone I knew in the community defaulted to multiple paths), you are still talking about creating more content than creating a fixed narrative. Many creatives walked away from the field, seeing this exponential increase in content creation.

Generative AI gives creatives back time to experiment and discover the grammar of interactive narrative

Generative AI can make content creation cheap, but more than that, it can free up the creative’s time – time to experiment.

Take creating an NPC (non-player character) in a new story world with Generative AI. With some basic prompting, you can create a tough, imposing bodyguard who also has a soft side for Japanese flower arrangements. You may not even know anything about flowers, but the Generative AI model can handle that. The Generative AI model can actually carry on a conversation about flowers for hours without breaking the suspension of disbelief.

The problem, as many modern-day experimenters in interactive narrative know, is that the NPC can easily break character. Questions of flowers can have them break out of the tough bodyguard role. It’s as if Generative AI prioritizes the conversation over character. Making content creation cheaper doesn’t solve everything, but it does make getting started and scaling much easier. I’m hopeful we will stumble upon a grammar for interactive narrative after a few years, or maybe months, given how quickly AI evolves, as early film pioneers established film grammar. Generative AI technology is advancing at an unprecedented pace, becoming increasingly accessible and conducive to experimentation. Instead of awaiting the next breakthrough, creatives should seize the moment and begin experimenting right now.

Leave a comment